Hugo Kauder’s Symphony No. 1

Notes by TŌN violinist Mae Bariff

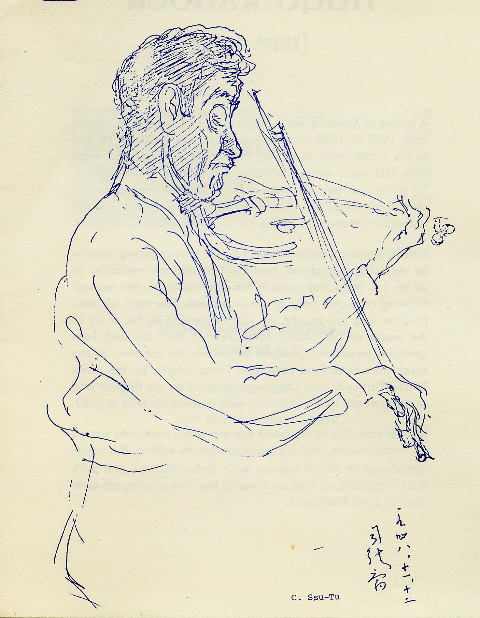

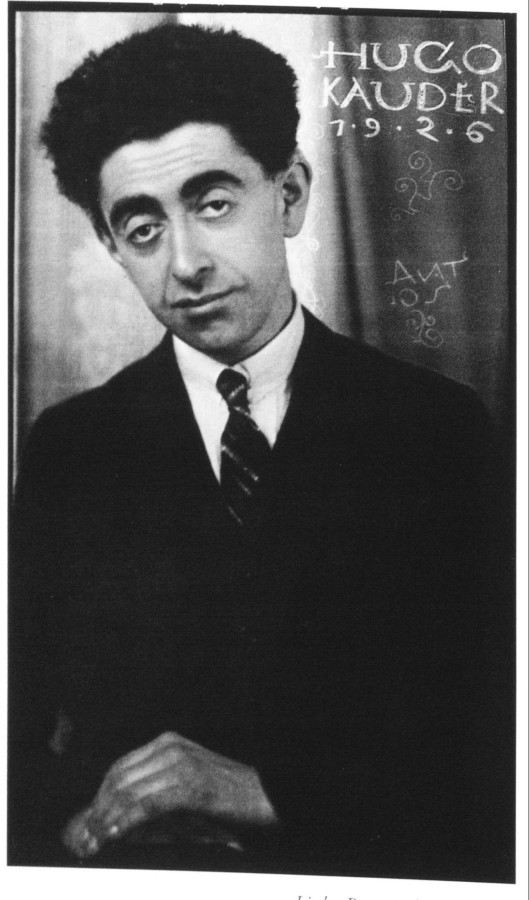

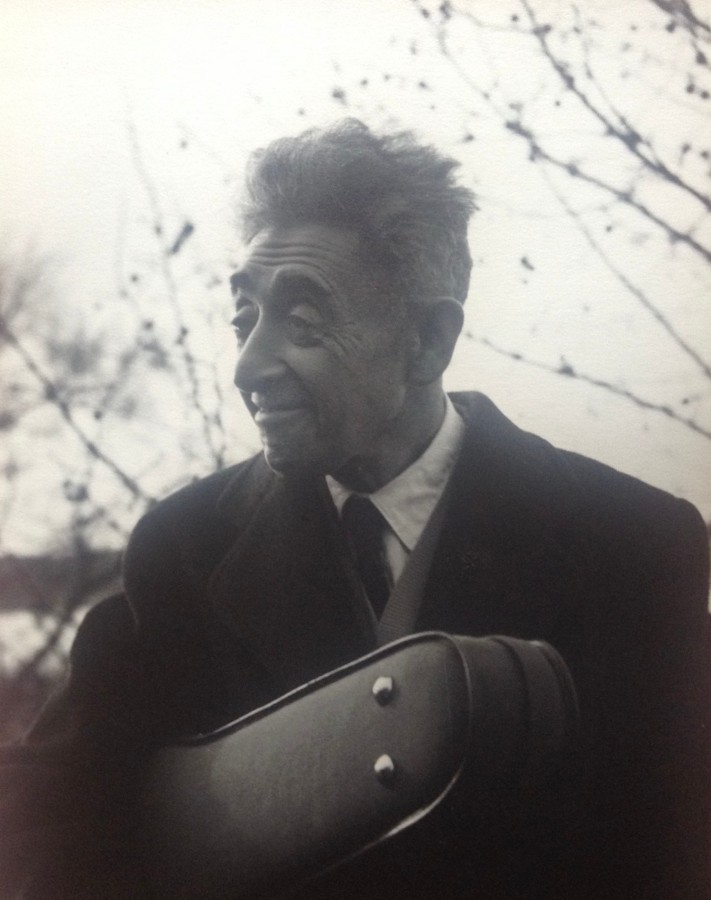

Hugo Kauder (1888–1972), born in Tobitschau, Moravia—now Tovočov, Czech Republic—studied violin as a boy and moved to Vienna in 1905 to pursue engineering; yet, his passion for music endured. Such passion led to successfully establishing himself as a musician, conductor, educator, writer, and emerging composer in Vienna. He composed his Symphony No. 1 in 1920–21 and dedicated it to Alma Mahler. Premiered in 1924 by the Vienna Workers Symphony, the First Symphony received considerable commendation and subsequently earned Kauder the prestigious City of Vienna Prize in 1928. Socio-geopolitical factors forced Kauder to leave Vienna in 1938—his compositions lost through war and displacement.

Composer/performer and college educator Karl Warner coordinated efforts to obtain autographed musical scores and performed an intensive editing and digitizing process to produce usable parts for performance. Warner also currently serves as manager of the Hugo Kauder Society. The Hugo Kauder Society aims to share Kauder’s music with future generations of musicians and listeners. Thank you to Hugo Kauder Society board members Norman Dee, David Goldblatt, David Levy, and Helen and Nina Kauder; former Hugo Kauder Society staff Rona Richter and Rron Karahoda; The Kauder Family; and Austrian musicologist Karin Wagner for generously supporting this project. I conducted a written interview on October 12, 2022 with Karl Warner and an extract from the edited transcript follows:

How did you locate the score?

Kauder fled Europe with two suitcases full of his music. The Kauder family kept and preserved most of his autograph scores or arranged to place them in library archives. I found the First Symphony score amongst these about two years ago and started editing and digitizing the first movement without much thought given to how or when it might be performed. Helen Kauder located a box amongst her father’s things that contained the original copied parts used for the 1924 performance of the Symphony. We also were contacted by someone in Germany who wished to authenticate an autograph Kauder score recently purchased at an auction. This turned out to be a two-piano draft/arrangement of the Symphony’s first movement. So, fate seemingly intervened with all of this lost related material showing up again around the same time.

What did you find most interesting about the restoration process?

At first glance, Kauder’s First Symphony is a somewhat conservative piece for 1920–21, but now it seems logical given where he went from there. Many hallmarks of his later style are in the work, in particular his ever-present mastery of organic motivic and melodic development and imitative counterpoint (often referred to as “Kauderpoint” by his students). Looking at the handwritten music makes those directly involved in its realization more immediate. The original hand-copied orchestral parts for the First Symphony feature notes and scribbles added by the musicians as part of their performance preparation. It is easy to imagine these pages being handled and placed on a stand long ago. A connection is made with [the musicians] even though they were of a different time and place. At the beginning, I trusted but didn’t quite know what the inherent qualities of the piece were and if it would stand on its own as a “great work of art.” I was encouraged by contemporary accounts of how well the piece was received when it was performed in 1924. As I got to know and experience the music, it always surprised me yet fulfilled all the expectations I set out with.

Did you encounter any challenges throughout the process?

I think I was naive at first about how long it would take or how difficult the work would be. Parts of the autograph score were difficult to read. Fortunately, we had backup sources available. Often I entered notes directly from the parts, although there were discrepancies and mistakes that needed to be correlated. I had to decide which additional performance markings to include. The autograph score has dynamic and tempo markings most likely made by conductor Leopold Reichwein. I wanted to keep Kauder’s original notation as much as possible and tried to include relevant details added later that he likely personally approved.

Recent currents in music performance aim to perform music from less frequently heard and/or known composers in addition to their frequently heard counterparts. Indeed a significant body of compositions from less frequently heard and/or known composers exists. In this sense, why Hugo Kauder?

In 1946 musicologist Edward Lowinsky eloquently wrote the following about Kauder’s music: “In much of our best modern music we feel the wild and hectic beat of our industrial machine age; its truthfulness rests in its reflecting the ever-growing mechanical aspect of our civilization. Kauder’s music seems to foreshadow a new humanism. It turns from the mechanical aspects of life to the organic, from the external powers that shape our existence to the inner spiritual forces. Kauder is not alone in taking this direction. But he follows this road with an inner assurance which gives his music a rare quietness and power.”

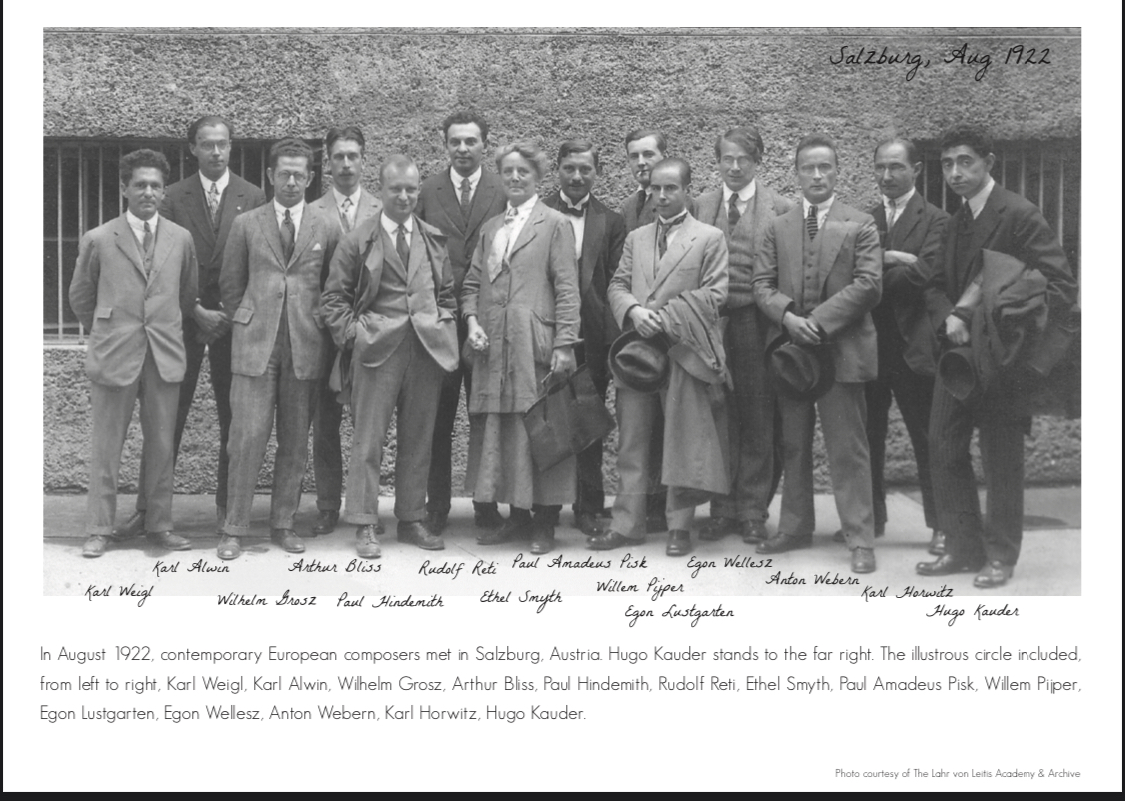

[Historically,] this particular generational group of Kauder’s Viennese friends and colleagues is very important. The work of the Second Viennese School is well documented, but studying these lesser-known composers provides a fuller, more detailed picture of a thriving and diverse community. Kauder’s generation was the last to inherit the immense legacy of a great musical city before all was disrupted and destroyed by the Nazis. I think audiences will experience all of this history flowing through the First Symphony. It is truly a “Viennese” piece, and one can hear reverberant echoes of Mozart, Haydn, Schubert, Beethoven, Brahms, and of course Mahler, whose music would have been very immediate and contemporary to Kauder.

Name a few things audiences can listen for in the symphony.

The first movement is built on the yearning, rising theme presented at the opening. Kauder organically builds powerful climaxes throughout the movement and expands the material through variation techniques including inversion (“upside-down” treatment of themes) and augmentation (rhythmic expansion of themes). The second movement was most likely not performed as part of the original premiere, and so audiences will finally hear this particular music for the first time. The music, set in buoyant rhythms with changing meters, is joyful and playful and at times demonic and intoxicating. The third slow, stately movement features beautiful arching lyrical lines that are built into several climaxes. In this movement, one most clearly hears the echoes of earlier Viennese composers mentioned previously. The music is introspective and contemplative, full of nostalgia and heart-felt longing. The fourth movement is an exciting technical tour-de-force, a masterful, strict passacaglia and fugue based entirely on the eight-bar steady chromatic line heard at the opening. The demonic, sulphuric character of the second movement returns, and one is constantly delighted as each new variation is presented over and builds upon the established, cycling, eight-bar harmonic structure.